At 82-years-old, Hayao Miyazaki presents his 12th cinematic masterpiece a decade after his previous movie, The Wind Rises, was released. Premiering in Japan on July 14, the Studio Ghibli production adopted a bold marketing approach—no trailers or publicity—showing Miyazaki’s ability to captivate audiences without conventional promotional tactics.

The film became the first original anime to top the North American box office with a $12.8 million opening. It also secured Miyazaki his Golden Globe Award nomination for best animated feature, sharing the spotlight with contenders like Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse, Elemental, The Super Mario Bros. Movie, Suzume, and Wish, ultimately resulting in his win. While Miyazaki had previously announced that The Boy and the Heron would be his last movie, some fans familiar with his history of announcing retirements, having done so thrice before in 1997, 2001, and 2013, are skeptical about whether this is true.

The Boy and the Heron is set in the early 1940s Japan during World War II. Voiced with depth and emotion by Soma Santoki in the original Japanese version and Luca Padovan in the English dubbing (a version where the audio of a film is changed from its original language, Japanese, to English), Mahito Maki’s narrative unfolds amidst the chaos of war and personal loss. Tragically orphaned by a hospital fire during a bombing raid on Tokyo, Mahito’s life takes a drastic turn as he deals with grief and displacement. His father’s remarriage to his late wife’s sister, Natsuko, causes Mahito to move to the countryside where his mother and Natsuko grew up. When a taunting heron suggests that his mother may still be alive, Mahito embarks on a quest that leads him to an abandoned tower, the last known location of his great-granduncle, who vanished years before.

“I feel like [The Boy and the Heron] was an amazing representation of grief…the way the heron keeps pestering Mahito and the fact that he kept having flashbacks to his mother is similar to how you never get a moment to yourself when grieving, no matter how hard you try to forget it,” explained freshman Liliana Torres.

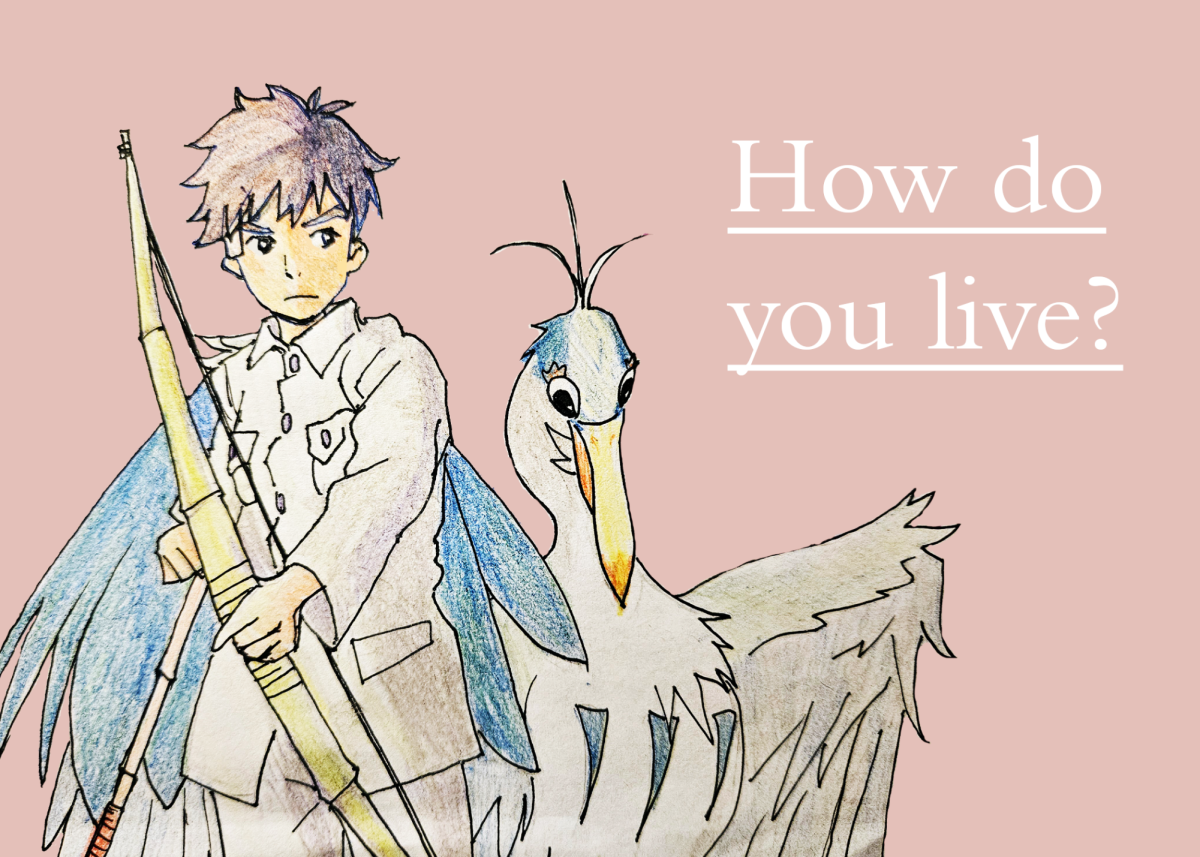

To truly grasp the film’s depth, it’s essential to understand its original title. While it’s called The Boy and the Heron in English, its Japanese title, How Do You Live?, is a nod to a 1937 novel by Genzaburo Yoshino. This book follows a 15-year-old named Koperu as he learns about life’s challenges. In the movie, the novel appears as a gift to Mahito from his late mother, inspiring his journey alongside the heron. Although the film isn’t directly based on Yoshino’s work, its inclusion became part of its theme. Drawing from Miyazaki’s own life experiences, like his father’s wartime work building planes, his family’s evacuation to the countryside, and his mother’s illness and subsequent passing when he was young, the film creates a story that feels familiar and realistic.

The film’s score was composed and performed by a long-time collaborator of Miyazaki, Joe Hisaishi. Hisaishi’s signature style shines through most of the tracks, characterized by haunting piano melodies that captivate with their simplicity. This musical choice enhances the film’s immersive experience, allowing the audience to remain enraptured by the breathtaking visuals and compelling storyline.

Unfortunately, The Boy and the Heron is not without its shortcomings. Primarily, the pacing in the first hour of the movie was rather slow. Meanwhile, the second half of the film is remarkably swift, resulting in underdeveloped aspects such as the nature of the alternate world, Mahito’s acceptance of Natsuko, and the complex concept of Mahito’s granduncle’s godhood. The supporting cast also lacks significant development, making it challenging for viewers to form attachments.

However, there are moments where the movie takes a humorous turn courtesy of the Parakeets, who manage to strike a balance between terror and humor.

“My favorite characters from [The Boy and the Heron] are the parakeets, they are creepy and aggressive, always carrying weapons, and trying to eat people,” said junior Esther Xuan. “It was interesting that they mimic human voices and are also violent.”

When compared with Miyazaki’s earlier works, the film falls somewhere in the middle to top range; it doesn’t surpass all of Miyazaki’s previous works but is still excellent. While the ending may feel somewhat complicated and confusing, scattered throughout are instances of undeniable brilliance. True to Studio Ghibli’s style, the film seamlessly blends whimsy with the harsh realities of life. The studio has never shied away from addressing themes of loss and grief, acknowledging that children inherently understand the world’s complexities.

As the credits roll, we are left to reflect on our own journeys and existence: How do we live? How will we navigate the trials and triumphs that define our lives? I, for one, just can’t wait for the time when Miyazaki retires from retirement once again.