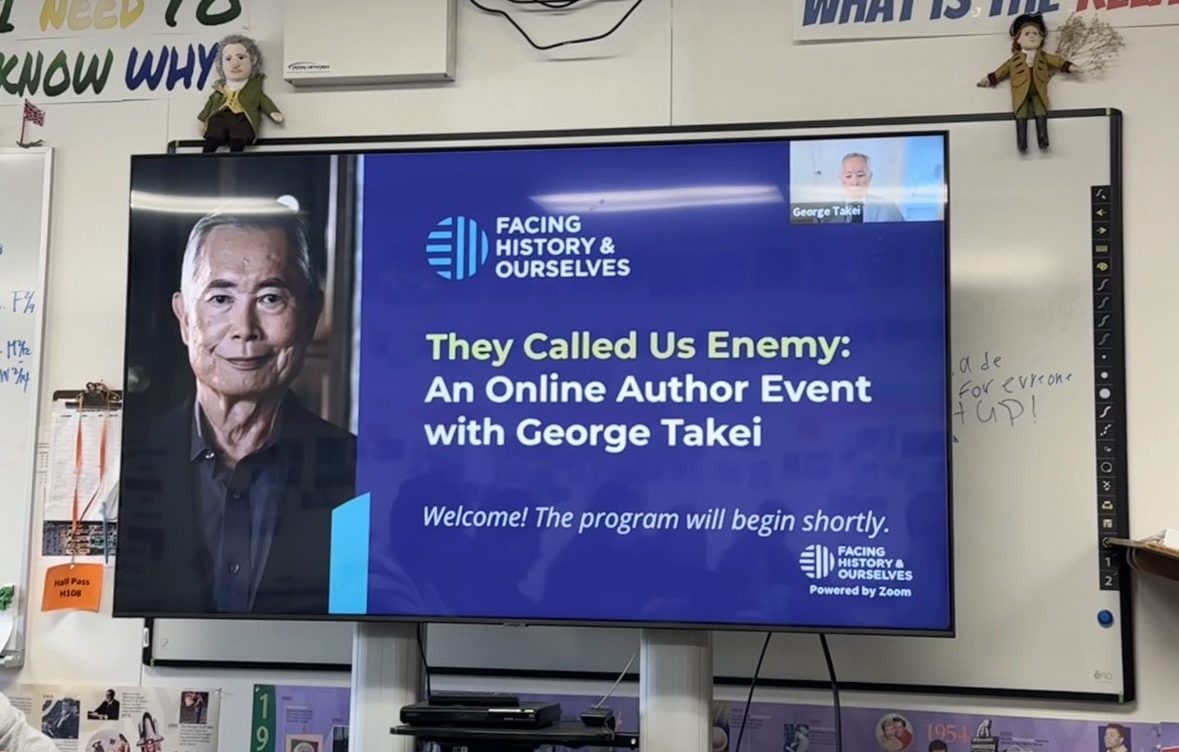

With the timer ticking away and anticipation building among the audience, a group of U.S. history students from Arcadia High School gathered in H108 during period 1 and period 2 on Feb. 13, joining thousands of students nationwide tuning in to a livestream featuring George Takei and his new graphic novel They Called Us Enemy, about Japanese American internment camps during World War II.

Born to Japanese American parents, George Takei is an American actor, activist, and author. You may recognize his name–if you’re a fan of Star Trek, you’ll be familiar with Takei from his role as Hikari Suru. What fewer people know about Takei, however, is his childhood proximity to a major historical event. During WWII, the then five-year-old was “interned” in two U.S. government-run concentration camps, where he bore witness to historical atrocities often omitted from modern textbooks. As he matured, he continuously explored his self-identity and used many platforms to fight for civil rights, LGBTQ rights, and marriage equality.

Now, Takei is 86-years-old, and taking a look back at the lessons he fears he has not fully addressed. Expressing his concern that this dark side of American history has not been sufficiently taught to young people, he explained why he chose to tell his childhood story about life in the camps in Arkansas and then at Tule Lake in graphic novel format.

“Even though I wrote about it, not many people know about it. I thought I needed to get young people to know about it. As a teenager, I loved reading comics. So I chose graphic novels of storytelling to tell the story,” said Takei.

“I wanted to inform Americans about our history, because I want to make our democracy a better democracy. If people don’t know about it, and it’s not taught at school, it’s no longer a history,” he continued.

Brian Fong, Program Director for Facing History’s California regional office and the moderator of the talk, started the livestream by emphasizing its purpose: to help younger generations recognize hidden history. He wishes to use this opportunity to inform neglected American history, and “ensure the lesson of history is preserved for future generations.”

Takei agreed on this idea, and began the talk by defining some prevalent, but often misunderstood terminologies. First, he accentuated how euphemisms entail replacing harsh or discomforting language with milder or more agreeable terms. Throughout WWII, the U.S. government heavily relied on euphemisms to describe the enforced detainment of Japanese Americans, obscuring the harsh reality of their incarceration. This tactic extended to phrases like “internment,” which, while legally sanctioned, carried ethically dubious connotations, especially when applied to Japanese immigrants who lacked American citizenship and were detained after the Pearl Harbor attack.

“The word euphemism is another euphemism for lies—that’s how euphemism defines and lies in history,” said Takei. “We weren’t the enemy; I was a five year old at that time. When we were incarcerated, I was outraged after they took our homes, destroy my father’s business, [but] I was too young to understand what’s happening around me. ”

Ultimately, the so-called “internment” of Japanese-Americans is rarely heralded as it is a painful chapter in American history.

Takei referred to that time period as a horrible time, because Japanese Americans were characterized as aliens due to Pearl Harbor. Victims of a combination of crazed war hysteria and widespread race discrimination, the Takei family were forced to move to a segregation camp for disloyalty. Sadness and shock permeated the once happy family, as they were characterized as “biologically disloyal” and made out to be criminals and enemies. Takei distinctly remembers the view he had of his parents during this time.

“My parents are my heroes. When we were incarcerated, I was too young to understand what was happening around me. But I remember their anguish. I remember the anguish, without truly understanding the reason why,” noted Takei.

Just like how many students appreciated this valuable lesson about true history, junior Darya Derakhshani specifically shared her insights.

“I think it really changed my perspective because as he was talking about, like, the Japanese Americans after World War II, they were heavily marginalized, and they didn’t talk about them in the textbook [except] maybe like two paragraphs,” said Derakhshani. “But they definitely deserve more. So, I think that in the George Takei interview, I was enlightened a lot, and I learned a lot about the Japanese American experience.”

It cannot be denied that Takei and his works serve as remarkably edifying pieces of writing, lending the youngest generations a first person perspective that is becoming all too rare; American moral shortcomings and failure to widely acknowledge the truth of the matter have robbed generations of school children a vital opportunity to learn, and have robbed an entire minority group of the recognition and recompense deserved.