Shrouded in the theater’s darkness, I became one of the scientists at Los Alamos who awaited, with both excitement and fear, the culmination of years of hard work. If this gadget worked, then we would be heralded as heroes who ended the most nightmarish war in history. But if we failed, we would be deemed fools who filled their heads with outlandish theories, producing nothing but wasted resources and efforts. The worst case scenario, however, was much more than just losing face. We would instead be villains who ignited the entire atmosphere, who changed the Earth into a desolate wasteland with only silence left as our critics.

The countdown reached zero, as a brilliant flash of light transformed the night into the day. An ominous cloud rose up from the ground, and only silence followed afterwards. Staring at our magnum opus, we knew the world would not be the same . . .

Perhaps it shouldn’t come as a surprise that when someone as renowned in the film world as Christopher Nolan works together with a talented cast, including Cillian Murphy, Matt Damon, Robert Downey Jr. and more, Oppenheimer emerges as a cinematic masterpiece that shakes the world even in 2023. Aside from its top-billing cast, Oppenheimer succeeds as a biopic as it not only crafts a story which maintains both thrill and accuracy, but also subverts the audience’s expectations throughout.

The first subversion comes from the way events are ordered in the film. Given the fact that Christopher Nolan directed this film, Oppenheimer does not follow a conventional chronological structure. The first half of the film feels like J. Robert Oppenheimer’s own recollection of events, consisting of jumps back and forth between the various periods of his life, while the latter half acts more akin to a documentary on the historical security hearings discussing Dr. Oppenheimer’s loyalty to the U.S. Though this approach is unconventional, the film does a good job helping the audience keep track of what is happening in each scene through the use of colors. Or in some cases, the absence of colors.

The subversion of colors compliments the subversion of chronology in several ways. As with any biopic, the film includes both the objective history of Dr. Oppenheimer and a subjective view from his eyes. As Nolan explained in an interview to Screenrant, “color scenes are subjective; the black-and-white scenes are objective.”

In the film, most scenes that chronologically precede the climatic detonation of the Trinity test (first detonation of a nuclear weapon) were in color, while scenes that depict events afterwards are in grayscale. This shift from the subjective to the objective not only made sense in the film’s own world (he was being interrogated and recalling his past), but it also reflected the audience’s greater knowledge of the later life of Dr. Oppenheimer, namely, his trial.

A final subversion comes with the climatic Trinity test. While the visuals of the explosion were no doubt spectacular and lived up to the expectation set, the impact of the event was unlike the short lived detonation as it only developed gradually. While the world may have changed with the Trinity test, Dr. Oppenheimer’s personal world was shaken only after the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Rather than the invention of the nuclear bomb, this was the reason he stated to President Truman that he “felt blood on his hands.”

Amidst the growing tensions in this world, it can be hard to imagine a time before the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction like nuclear weapons. Oppenheimer is a much-needed film that reminds us of the work of those who first created these weapons and, more importantly, the moral and ethical dilemmas that arise from new technologies. All in all, Oppenheimer proved to be a captivating biopic exploring the life of J. Robert Oppenheimer and his invention that appeals to both casual viewers and serious historians.

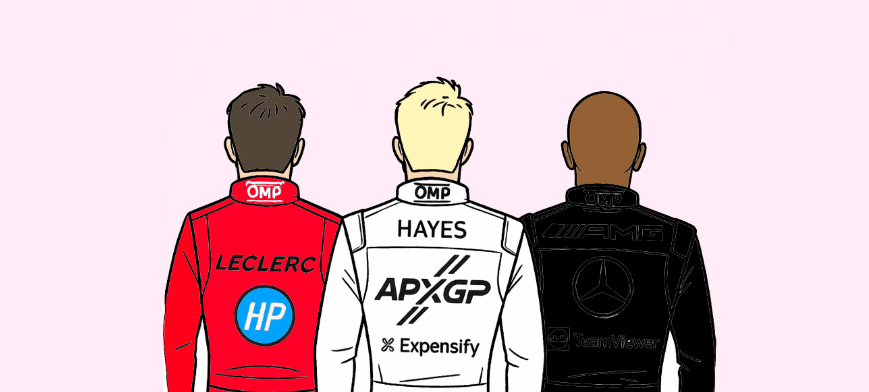

Graphic courtesy of Rachel Lee