Most people are familiar with the character of “Barbie”, in both doll and movie form. Whether you had the doll growing up, or joined in on the Barbie Movie fever flooding movie theaters this summer, there’s a face to the name. If even hearing the word conjures an image of plastic with lipstick or a certain Australian actress, maybe you haven’t thought much about it.

Few people are quite so familiar with the purpose of “Barbie;” not a fun and adorable doll, or a comical and quirky design of girlhood. The epitome of her purpose (using “her” tentatively) and her role in creation, was to be perfect. A kind of perfect that certainly doesn’t exist. But modern-moviegoers certainly seem to think this has been well-accomplished. Viewers in 2023 tout the Barbie movie, a billion-dollar box-office smash hit, as one of the best movies of the decade. In short, she’s back to her perfect roots, beloved by all. But the deeper ideological issue with a perfect doll of a perfect girl, to me, marked every part of the film’s hour and 45 minutes. Pseudo-feminism and cheap jokes made me question the overwhelming love for Barbie. As fellow audience members cracked up in the theater over Margot Robbie being deemed “too perfect looking” to sell a joke about physical insecurities, I was left wanting more. More depth, more explanation. At least in these regards, Barbie took a big swing at a grandiose depiction of 21st century modern feminism. And missed.

Most people didn’t realize the nature of Barbie before seeing it. Instead of the silly and cute comedy many were expecting in the early months of promotion, the movie took a courageous leap into questions of female identity and humanity. “Girlhood,” as the movie defines it, was a major theme, in the light of loss. But though deep themes were discussed, I believe many viewers failed to consider anything about the movie besides a one word-description of “feminist.” Failing to form original opinions on the reckoning with patriarchy, struggle with personal identity as female-identifying, and embracing the emotions of change, bred a pink mob of mindless praisers. Barbie spent its first few weeks in the box office overhyped.

It took a long time to solidify my main criticism of the movie; small things about the film that irked me built up over time, and as my friends raved, I still wondered. What was the one, main facet of Barbie that had kept me from enjoying it like everyone else? I eventually realized—what I hadn’t liked was writers that I had never met, actors who lived so differently from me, and a director who I knew nothing about telling me explicitly what my life should mean. According to the roles laid out in the movie, I could be young and angry, brainwashed and complacent, or “break out of the box” and suddenly know all the secrets of life. But of course, at least I’m not a worthless man.

Cheap humor also made the comedy aspects of Barbie gimmicky and a little gross. Even the parts of the film meant to elicit uproarious laughter and internet memes seemed to play on stereotypes and cliches. For example, a (censored) F-bomb is dropped for comedic purposes, though seemingly not having much of a purpose or commentary behind it. Sexual harassment is made into a joke; though apparently Barbie throwing a punch in self-defense makes it “worth it” for the laughs. A whole montage early on in the movie is even dedicated to Kens yelling about “beaching each other off.” A particular favorite of audiences seemed to be Barbie’s visit to teenage Sasha’s high school, where Sasha and her Gen-Z symbolizing friends lash out at her. Though the impassioned speech was meant to showcase the jaded disillusionment of the youngest generation of girls, I could only think about the way that Sasha’s arguably cruel words were played for laughs, when it should have been where her struggle was acknowledged but her approach condemned.

Additionally, convoluted feminism muddled director Greta Gerwig’s purpose for me. A striking instance: an “uplifting” scene about female empowerment and control was undercut by the nagging presence of institutionalized and traditional expectations of the meaning being “pretty.” As the Barbies hatch a plan to take back control of their home from the men, the script’s attempt to subvert stereotypes accidentally plays right into them; the Barbies do makeup and pretty clothing and act dumb, seemingly acknowledging the underestimation made of women by men. But in doing so, the scene plays more like a parody than a commentary, and people were kept wondering what statement was actually being made about these societal expectations. Overall, the tone taken to address such a serious topic made the messaging feel unserious.

Token-feminism terminology also undermined the message for me. Some monologues almost seemed like a compilation of “top 20 feminist mantras” taken off the internet and copied into the script. For example, complaining about the injustice of high-heeled shoes is a valid cause, but pointing it out as part of the perfect Barbie persona felt like pandering to the issue when it was shown in comparison to a flat-footed “weird Barbie.”

The cliches in the film and its popular praise truly go hand in hand—Barbie-related posts and comments seem to disproportionately feature expressions like “iconic” and “girlboss,” lending an almost-cringey air to what likely includes valid and sophisticated praise. A prime example of a cliche was Barbie proudly pronouncing that she was going to see her gynecologist; the joke didn’t sit right with me, and didn’t seem to actually offer any original commentary beyond what scriptwriters likely knew the audience wanted to hear.

I did have two favorite lines however, both very strikingly profound: “Humans only have one ending. Ideas live forever,” and “We mothers stand still so our daughters can look back and see how far they have come.” Both of these moments touched on the intricacies of identity in a way that had been half-heartedly alluded to the rest of the movie. Another personal highlight was Billie Eilish’s contribution to the soundtrack, with her song “What Was I Made For,” that captured what I thought to be more appropriately open-ended than the movie’s script itself.

So what I applaud the movie for is trying to answer questions about feminism, sexism, identity, and self-worth when no one else has even tried. And for giving a group of people, exhausted with the very same world the movie reckons with, the excuse to be happy in a theater, wearing a pink cowboy hat.

So in the end, I agree. I agree with Greta Gerwig’s righteous stand against gender-based double standards. I agree with the film’s humble acceptance of the meaning behind being human. I enjoyed Billie Eilish’s honest pondering in a comforting song. I agree, enjoy, and relate to so much of this movie, as a girl growing up today. But I can’t blindly accept what is offered to me as an explanation of my heart and life. Barbie was right on the money, a billion dollars to be exact, while aiming at society’s ache for a “why.” Of course every child, young girls especially, want to know what their life will be about, and why. But all they got right was acknowledging the questions, without providing answers. What does it mean to be perfect? What part does happiness play in a life, without sadness? Why isn’t there equality, and who decided on the sides of the argument? Greta Gerwig isn’t at fault for not being able to tell us things that can’t be answered so directly, and we’ve been wondering about for as long as we’ve had cultivated agriculture. The Barbie movie can act like a mother, getting us as far as it’s able, but not possessing the ability to tell us the meaning of our lives. As much as Greta Gerwig and Barbie might have tried, questions like these have to be answered with all the knowledge collected in a lifetime. For now, asking those questions is how we face life.

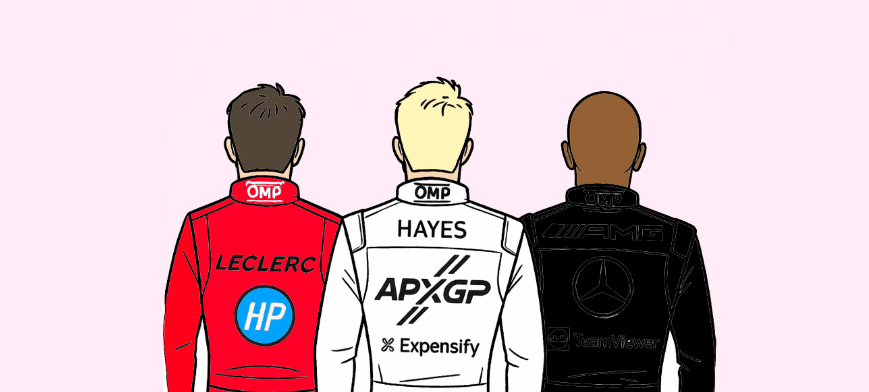

Graphic courtesy of Rachel Lee