Kumon, piano, and ballet: the three things that my childhood constantly revolved around. Everyday after school, while others goofed around and watched Wild Kratts and Curious George, I would be forcefully sent to one of these above activities. My parents’ reasoning for it? “It will be useful later on…when you’re applying for college.”

I was a dime a dozen. A majority of my Chinese American friends had the same schedule. For us, extracurriculars after school went beyond mere expectations. If I met another kid who wasn’t attending Kumon, it made me physically ill. My parents promised me glory if I could finish a math packet, play a sonata, and do the splits within the same hour.

This Chinese cultural belief perpetuates a harmful societal pressure on parents to start their kids’ academic journey from a young age. In turn, family dynamics, a child’s formation of identity, and mental health are negatively impacted.

Most know that the road to college is an arduous one for kids around the world, but comparatively, it’s much more demanding for Chinese Americans to stand out to admission boards. And college admission for students of Chinese descent isn’t getting easier. In the hopes of getting admitted to private prestigious colleges, students who identify as Asian must score an average of 270 points higher than Black applicants and 100 points higher than White applicants on the SAT.

For many students, admission into a prestigious college is viewed as a ticket to a higher social status or the opening to a better future. In the hopes of securing a college admission spot, parents make sure that their kids “don’t lose the race at the starting line.” You might assume that a widely popularized ideology embraced by numerous Chinese families would make for a highly advantageous social progress. But, it’s actually quite the opposite.

Often prescribed the term “tiger moms,” parents who push their children to speedrun as much challenging content as possible believe that getting ahead in credits means students are ahead in everything. It’s with this belief that parents seek security in the world’s multibillion-dollar industry of academic tutoring (bǔxíbāns). However, bǔxíbāns, or cram schools, only increase mental stress. Restless parents drive their kids to multiple different academic sessions; some even have to work multiple jobs to keep up with costly tutor fees.

Over time, this anxiety erodes the parent-child relationship. Parents feel as if their sacrifices will be rewarded through their preferred outcome of academic success.Thus, when a child falls short of their parent’s vision, parents feel as if their efforts are in vain and children remain starved of parental validation, creating deeper tensions in the home. In order to get to the finish line, parents force themselves to invest their full time into their children, with their unfulfilled wishes introducing greater issues to the family.

The most prevalent—and often stereotyped—career expectations in Asian households include doctors and lawyers. Jobs that fall outside of these fields are generally frowned upon, with children taking on their parents’ vision of success and worth. In particular, material success directly aligns with the belief of “not losing the race at the starting line,” since many families see wealth and status as indicators of achievement.

Another prevalent concept among many Asian households is “filial piety.” Which refers to how children are expected to honor and obey their parents through every decision in their life. Disobedience results in bitter confrontations, whether over a small action like forgetting to cap a jar or asking to spend time with friends. Like other peers, I personally felt that my personal struggles in school were not just my own, but rather a larger shame that dishonored my ancestors. It was this duty that encouraged me to take Pre-Algebra and Algebra 1 in one year. It was this expression that encouraged me to surround myself with the best of the best. From all the unnecessary stress I put onto myself, I began to lose my academic passion as I was learning ad nauseum.

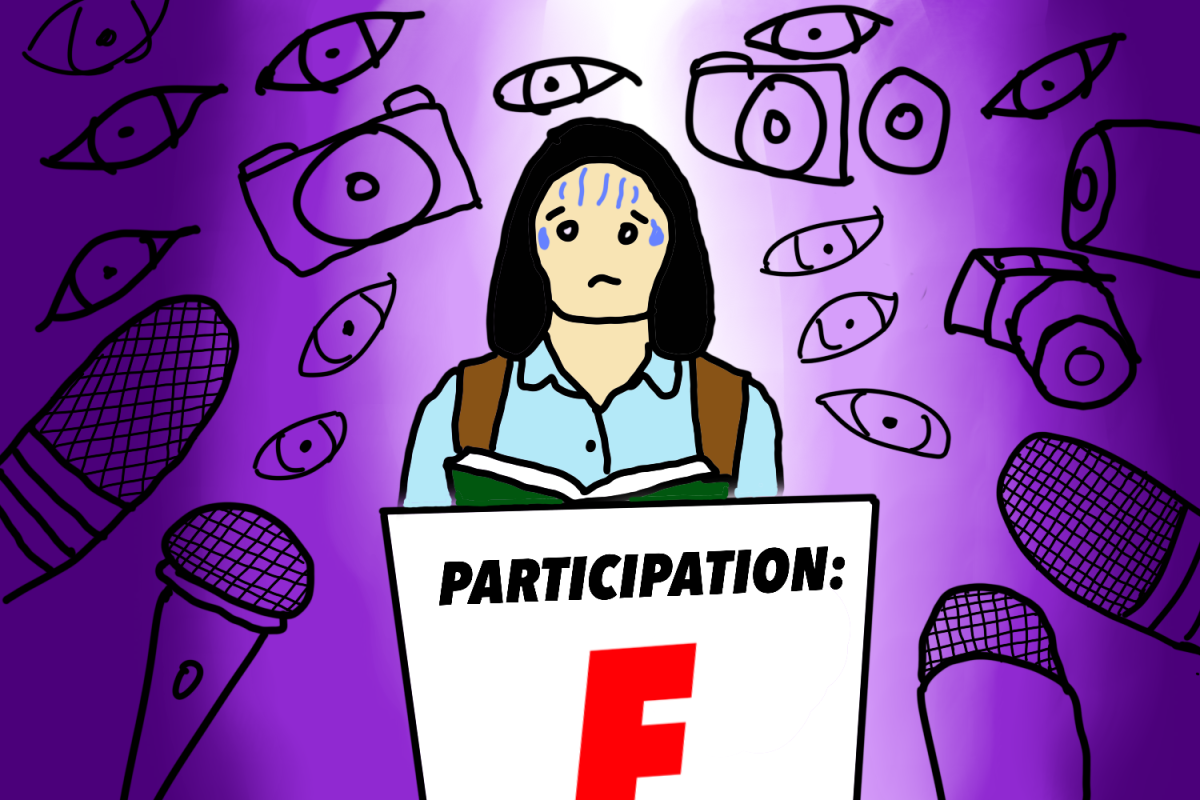

Stress from academics is one of the greatest reasons that Chinese American students are finding themselves struggling with their mental health. For many, getting an A- on a test is the end of the world. For others, having a 3.9 GPA means they are not trying their best.

Peter Pan, a current Ph.D. candidate in computer science quoted in an article on cram schools and the Chinese educational system, said, “I didn’t dare to tell my parents even when I scored 99 out of 100 on my test.”

In fact, there are trending Quora and Reddit discussions where many students ask questions like: “How do I tell my Asian parents I received a bad grade?” or “What’s the best way to tell your parents that you got a really bad grade on a test?” The responses include kind-hearted adults reminding readers that grades don’t define anyone, and other Asian students commenting “your dead, lol. [sic]”

Without a doubt, childhood is the most important aspect of a young person’s life: building curiosity, making cherishable memories, and starting to have a sense of what they might do for a living. However, a childhood filled with tutors, cram schools, and piles of homework is far from ideal in those formative years.

On a larger scale, the mentality focused on getting ahead generates a lack of passion among children, which has a negative impact on the workforce and society as a whole. One societal dilemma is that many talented kids are unavailable to society’s workforce since they refuse to contribute their knowledge to society. Many students think that they have already fulfilled the requirements needed to succeed and no longer have motivation to learn. Their absence of motivation hinders the mastering professions and roles and also gives a false sense of completion to lifelong learning.

The point of learning should not be to get a headstart over other students to secure a spot at the top college of your choice, but rather about embracing the negative and positive experiences of your academic journey. Simulating a race for the top has caused parents to pour too much into college admissions and children to give up on their dreams to pursue competitive studies that will earn them material success.

Instead of “trying to win the race,” parents should try to strike a balance between fostering a healthy perspective of success and encouraging educational growth. If not, students will find themselves feeling overwhelmed with the fear of falling short to expectations.

This summer, I am rediscovering motivation, but this time without “filial piety” defining my choices. This semester, I’ve decided against taking any APs or Honors, and by doing so, I am also taking away the potential burden these classes bring. I am well aware that by taking regular classes, I will be falling behind my peers; nevertheless, this is the sole path available to me for a fresh start and personal renewal. On top of that, instead of choosing both language and science, I have decided to take a year off and choose a fun extracurricular class. Just within the first few days of school, I no longer feel the same stress I felt last year. My school day is now starting to fill with cherishable memories rather than constant worry about grades. This shift in focus led me to understand the importance of a healthy educational journey.

Photo courtesy of ELEANOR GLADSON-PANG